These trailblazing clinicians, researchers, inventors, and advocates broke barriers, shattered stereotypes, and advanced medicine in this country and beyond.

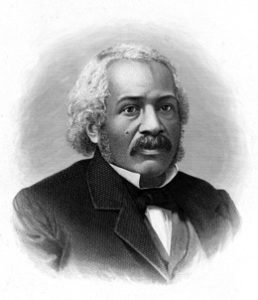

James McCune Smith, MD (1813 – 1865)

Born into slavery in New York City in 1813, James McCune Smith, MD, was a man of firsts. In 1837 at the age of 24, he became the first Black American to receive a medical degree—although he had to enroll at the University of Glasgow Medical School because of racist admissions practices at U.S. medical schools. And that was far from his only groundbreaking accomplishment. He was also the first Black person to own and operate a pharmacy in the United States and the first Black physician to be published in U.S. medical journals.

Smith used his writing talents to challenge shoddy science, including racist notions of African Americans. Most notably, he debunked such theories as Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia. Smith was a staunch abolitionist and friend of Frederick Douglass. He contributed to Douglass’ newspaper and wrote the introduction to his book, My Bondage and My Freedom. Smith died about three weeks before the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery in the United States.

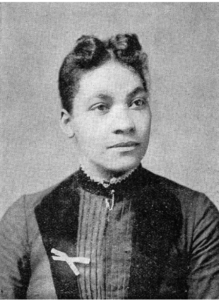

Rebecca Lee Crumpler, MD (1831 – 1895)

In 1864, Rebecca Lee Crumpler became the first Black woman in the United States to receive an MD degree. She earned that distinction at the New England Female Medical College in Boston, Massachusetts—where she was also the institution’s only Black graduate. Prior to earning her medical degree, Crumpler had worked as a nurse and “sought every opportunity to relieve the suffering of others.”

After the Civil War, Crumpler moved to Richmond, Virginia, where she worked with other Black doctors who were caring for formerly enslaved people in the Freedmen’s Bureau. While she faced sexism and other forms of harassment, Crumpler ultimately found the experience transformative. “I returned to my former home, Boston, where I entered into the work with renewed vigor, practicing outside, and receiving children in the house for treatment; regardless, in a measure, of remuneration,” she wrote.

Crumpler also wrote A Book of Medical Discourses: In Two Parts. Published in 1883, the book is one of the first publications about medicine written by an African American. The book addresses children’s and women’s health and is written for “mothers, nurses, and all who may desire to mitigate the afflictions of the human race.”

Daniel Hale Williams, MD (1856–1931)

After apprenticing with a surgeon, Daniel Hale Williams earned a medical degree and started working as a surgeon in Chicago in 1884. Because of discrimination, hospitals at that time barred Black doctors from working on staff. So Dr. Williams opened the nation’s first Black-owned interracial hospital.

Provident Hospital offered training to African American interns and established America’s first school for Black nurses. On July 10, 1893, Williams successfully repaired the pericardium (the sac surrounding the heart) of a man who had been stabbed in a knife fight. The operation is considered to be the first documented successful open-heart surgery on a human, and Williams is regarded as the first African American cardiologist.

He went on to cofound the National Medical Association and became the first Black physician admitted to the American College of Surgeons.

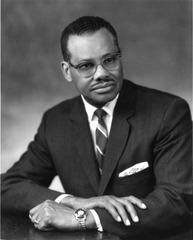

Leonidas Harris Berry, MD (1902–1995)

Even as a renowned gastroenterologist, Leonidas Harris Berry, MD, faced racism in the workplace. Berry was the first Black doctor on staff at the Michael Reese Hospital in Chicago, Illinois in 1946, but he had to fight for an attending position there for years. “I have spent many years of crushing disappointment at the threshold of opportunity,” he wrote to the hospital’s trustee board committee in his final plea, “keeping my lamps trimmed and bright for a bride that never came.” He was finally named to the attending staff in 1963 and remained a senior attending physician for the rest of his medical career.

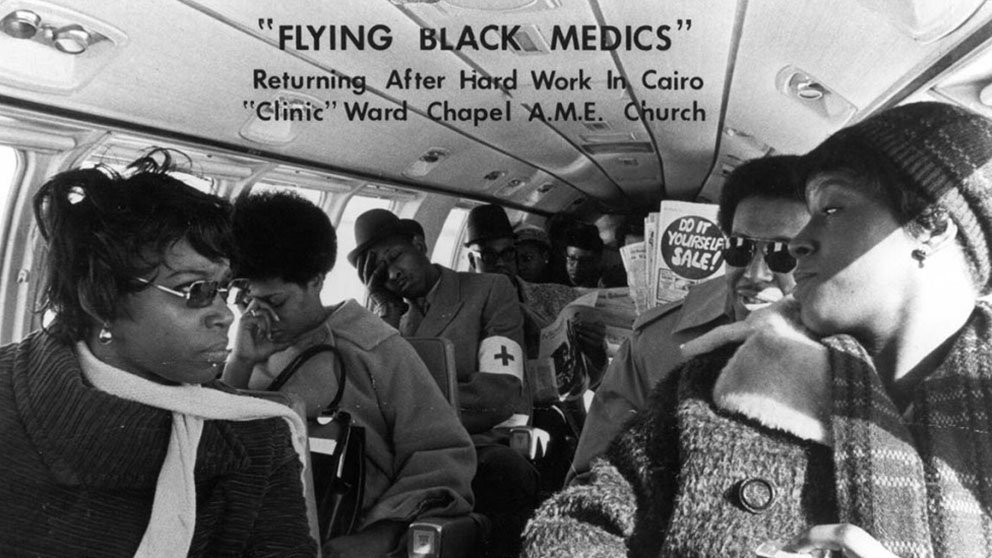

In the 1950s, Berry chaired a Chicago commission that worked to make hospitals more inclusive for Black physicians and to increase facilities in underserved parts of the city. But his dedication to equity reached bar beyond the clinical setting: He was active in a civil rights group called the United Front that provided protection, monetary support, and other assistance to Black residents of Cairo, Illinois who had been victims of racist attacks. In 1970, he helped organize the Flying Black Medics, a group of practitioners who flew from Chicago to Cairo to bring medical care and health education to members of the remote community.

The Flying Black Medics, founded by Leonidas Harris Berry, MD, return from providing medical care and education to residents of Cairo, Illinois in 1970.

Charles Richard Drew, MD (1904–1950)

Known as the “father of blood banking,” Charles Richard Drew, MD, pioneered blood preservation techniques that led to thousands of lifesaving blood donations. Drew’s doctoral research explored best practices for banking and transfusions, and its insights helped him establish the first large-scale blood banks. Drew directed the Blood for Britain project, which shipped much-needed plasma to England during World War II. Drew then led the first American Red Cross Blood Bank and created mobile blood donation stations that are now known as bloodmobiles. But Drew’s work was not without struggle. He protested the American Red Cross’ policy of segregating blood by race and ultimately resigned from the organization.

Despite his renown for blood preservation, Drew’s true passion was surgery. He was appointed chairman of the Department of Surgery and Chief of Surgery at Freedmen’s Hospital (now known as Howard University Hospital) in Washington, D.C. He also became the first African American to be appointed an examiner for the American Board of Surgery. Throughout his life, Drew went to great lengths to support young African Americans pursuing careers in the medical discipline.

Drew’s innovative work was recognized by awards and honors including the 1942 E.S. Jones Award for Research in Medical Science from the John A. Andrew Clinic in Tuskegee, AL; an appointment to the American-Soviet Committee on Science in 1943; the 1944 Spingarn Medal from the NAACP for his work on blood and plasma; honorary doctorates from Virginia State College (1945) and Amherst College (1947); and election to the International College of Surgeons in 1946.

Jane Cooke Wright, MD (1919–2013)

The daughter of one of the first Black American graduates of Harvard Medical School, Jane Cooke Wright grew up with an avid interest in healthcare. Her father, Dr. Louis Wright, was also the first Black doctor appointed to a staff position at a municipal hospital in New York City, and in 1929, the city hired him as police surgeon—the first African American to hold that position.

After earning her medical degree, Dr. Jane Cooke Wright worked alongside her father at the Cancer Research Foundation in Harlem, which her father established in 1948. Together, father and daughter researched chemotherapy drugs that led to remissions in patients with leukemia and lymphoma.

In 1952, when her father died of tuberculosis, Wright became the head of the Cancer Research Foundation at age 33. She created an innovative technique to test the effect of drugs on cancer cells by using patient tissue rather than laboratory mice. She advanced to work as the director of cancer chemotherapy at New York University Medical Center, and she was an associate dean at New York Medical College.

The New York Cancer Society elected Wright as its first woman president in 1971. Her research helped transform chemotherapy from a last resort to a viable treatment for cancer.

Otis F. Boykin (1920–1982)

Born in Dallas, Texas in 1920, Otis Boykin hurdled many obstacles to pursue his life’s calling—inventing electronic innovations.

Born in Dallas, Texas in 1920, Otis Boykin hurdled many obstacles to pursue his life’s calling—inventing electronic innovations.

During his career, Boykin patented 28 electronic devices. His many inventions included a chemical air filter, a burglarproof cash register, and various resistors for electronic components that made the production of televisions and computers more affordable. His most famous invention, however, was a control unit for the cardiac pacemaker, which used electrical impulses to stimulate the heart and create a steady heartbeat.

In a tragic twist of fate, Boykin died in 1982 as a result of heart failure. The long-lasting effects of his pioneering ingenuity are still felt today in the medical world and beyond.

Louis Wade Sullivan, MD (b. 1933)

Louis Wade Sullivan, MD, grew up in the racially segregated rural South in the 1930s. There, he was inspired by his doctor, Joseph Griffin. “He was the only Black physician in a radius of 100 miles,” Sullivan said. “I saw that Dr. Griffin was really doing something important and he was highly respected in the community.”

Louis Wade Sullivan, MD, grew up in the racially segregated rural South in the 1930s. There, he was inspired by his doctor, Joseph Griffin. “He was the only Black physician in a radius of 100 miles,” Sullivan said. “I saw that Dr. Griffin was really doing something important and he was highly respected in the community.”

Over the decades, Sullivan became an equally profound source of inspiration. The only Black student in his class at Boston University School of Medicine, he would later serve on the faculty from 1966 to 1975. In 1975, he became the founding dean of what became the Morehouse School of Medicine—the first predominantly Black medical school opened in the United States in the 20th century. Later, Sullivan was tapped to serve as secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, where he directed the creation of the Office of Minority Programs in the National Institutes of Health’s Office of the Director.

Sullivan has chaired numerous influential groups and institutions, from the President’s Advisory Council on Historically Black Colleges and Universities to the National Health Museum. He is CEO and chair of the Sullivan Alliance, an organization he created in 2005 to increase racial and ethnic minority representation in health care.

Marilyn Hughes Gaston, MD (b. 1939)

In a pivotal experience while working as an intern at Philadelphia General Hospital in 1964, Marilyn Hughes Gaston, MD, admitted a baby with a swollen, infected hand. The baby suffered from sickle cell disease, which hadn’t occurred to Gaston until her supervisor suggested the possibility. Gaston quickly committed herself to learning more about it, and eventually became a leading researcher on the disease, which affects millions of people around the world. She became a deputy branch chief of the Sickle Cell Disease Branch at the National Institutes of Health, and her groundbreaking 1986 study led to a national sickle cell disease screening program for newborns. Her research showed both the benefits of screening for sickle cell disease at birth and the effectiveness of penicillin to prevent infection from sepsis, which can be fatal in children with the disease.

In a pivotal experience while working as an intern at Philadelphia General Hospital in 1964, Marilyn Hughes Gaston, MD, admitted a baby with a swollen, infected hand. The baby suffered from sickle cell disease, which hadn’t occurred to Gaston until her supervisor suggested the possibility. Gaston quickly committed herself to learning more about it, and eventually became a leading researcher on the disease, which affects millions of people around the world. She became a deputy branch chief of the Sickle Cell Disease Branch at the National Institutes of Health, and her groundbreaking 1986 study led to a national sickle cell disease screening program for newborns. Her research showed both the benefits of screening for sickle cell disease at birth and the effectiveness of penicillin to prevent infection from sepsis, which can be fatal in children with the disease.

In 1990, Gaston became the first Black female physician to be appointed director of the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Bureau of Primary Health Care. She was also the second Black woman to serve as assistant surgeon general as well as achieve the rank of rear admiral in the U.S. Public Health Service. Gaston has been honored with every award that the Public Health Service bestows.

Patricia Era Bath, MD (b. 1942)

Patricia Era Bath, MD, was the first African American to complete an ophthalmology residency. As an intern in New York City in the 1960s, Bath noticed a troubling trend. The rates of blindness and visual impairment were much higher at the Harlem Hospital’s eye clinic, which served many Black patients, than at the eye clinic at Columbia University, which mostly served white patients. That observation spurred her to conduct a study that found twice the rate of blindness among African Americans compared with whites. Throughout the rest of her career, Bath explored inequities in vision care. She pioneered the discipline of community ophthalmology, which approaches vision care from the perspectives of community medicine and public health.

Bath blazed trails in other ways as well, co-founding the American Institute for the Prevention of Blindness in 1976, which supports programs that protect, preserve, and restore eyesight. Bath was also the first woman appointed Chair of Ophthalmology at a U.S. medical school, at the University of California, Los Angeles David Geffen School of Medicine in 1983. In 1988, she was the first Black female physician to receive a medical patent in for the Laserphaco Probe, a device used in cataract surgery.

Alexa Irene Canady (b. 1950)

In 1981, Alexa Irene Canady, MD, became the first Black neurosurgeon in the United States. In earlier years, she had nearly dropped out of college, citing a lack of confidence. But she persevered and went on to achieve wild success in her medical career.

In 1981, Alexa Irene Canady, MD, became the first Black neurosurgeon in the United States. In earlier years, she had nearly dropped out of college, citing a lack of confidence. But she persevered and went on to achieve wild success in her medical career.

Just a few years after becoming America’s first Black neurosurgeon, she rose to the position of Chief of Neurosurgery at Children’s Hospital of Michigan and worked for decades as a successful pediatric neurosurgeon. In 2001, just as she was contemplating hanging up her scrubs for retirement in Florida, Canady observed that Sacred Heart Hospital in Pensacola was severely lacking in pediatric neurosurgery services and decided to continue her practice there part-time. Canady has been widely recognized for her patient-centered approach to care, a practice to which she attributes much of her success. “I was worried that because I was a Black woman, any practice opportunities would be limited.” However, “by being patient-centered, the practice growth was exponential.”

Regina Marcia Benjamin, MD, MBA (b. 1956)

Regina Marcia Benjamin, MD, MBA, may be best known for her tenure as the 18th U.S. Surgeon General. Appointed by President Barack Obama, she served from 2009 to 2013 in dual roles as the nation’s physician and as first chair of the National Prevention Council, a body of 17 federal agencies responsible for developing plans to improve health and well-being in the United States.

Dr. Benjamin championed public health long before her career reached the highest levels of our nation. After earning her doctor of medicine degree at the University of Alabama at Birmingham in 1984, she served her internship and residency in family practice at the Medical Center of Central Georgia at Macon. From 1990 to 1995, she was a medical director at several nursing homes, and in 1993 she went on a medical mission to Honduras. From 2000 to 2001, she was responsible for the USA Telemedicine distance learning program, which offers medical education and specialty health care to patients and clinicians in rural and medically underserved areas through a private telecommunications network.

Dr. Benjamin continuously serves rural communities in the South. She is the founder and CEO of BayouClinic in Bayou La Batre, Louisiana, which provides clinical care, social services, and health education to residents of the small Gulf Coast town. She has rolled up her sleeves and rebuilt the clinic several times, including after damage inflicted by Hurricane Georges in 1998, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, and a fire in 2006. Facing the destruction of her clinic after Hurricane Georges, Dr. Benjamin continued to serve her patients by making house calls in her 1988 Ford pickup. Of her motivation in the face of so many obstacles, Benjamin explains, “I hope I make a difference one person at a time—by making a patient feel better, by being able to tell a mother that her baby is going to be okay. Whether her baby is four or forty-four, the look on the mother’s face is the same. I also hope that I am making a difference in my community by providing a clinic where patients can come and receive health care with dignity.”

Sources

Rauf, Don (2021, February 4). 12 Black American Pioneers Who Changed Healthcare. EverydayHealth.com. https://www.everydayhealth.com/healthy-living/african-american-pioneers-who-changed-healthcare/

Haskins, Julia (2019, February 25). Celebrating 10 African-American medical pioneers. AAMC.org. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/celebrating-10-african-american-medical-pioneers

Biography: Dr. Regina Marcia Benjamin. Changing the Face of Medicine. https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_31.html